Hi there, and welcome. This content is still relevant,

but fairly old. If you are interested in keeping up-to-date with similar

articles on profiling, performance testing, and writing performant

code, consider signing up to the Four Steps to Faster Software newsletter. Thanks!

This is a continuation of my previous post, in which we follow the path of an inbound multicast packet to the user application.

At the end of the last post, I mentioned that application back-pressure was most likely to be the cause of receiver packet-loss. As we continue through the code path taken by inbound packets up into user-land, we will see the various points at which data will be discarded due to slow application processing, and what metrics can shed light on these events.

First of all, let's take a quick look at how a received data packet is matched up to its handler function.

We can see from the stack-trace below that the top-level function calls when dealing with the packets are

The protocol-to-handler mapping can be viewed in the file

Comparing against this reference, it is clear that the kernel reads the value of the ethernet frame's

So our inbound packet will be processed by the capture hooks, even if no packet capture is running (this then must presumably be very cheap), before being passed to the correct protocol handler, in this case

As discussed previously, each socket on the system has a receive-side FIFO queue that is written to by the kernel, and read from by the user application.

Before calling the

Assuming that the packet is not dropped by a filter,

In the internals of the

Simple validation performed at this point includes packet-length check and checksum. Failure of these checks will cause the relevant statistics to be updated in the global udp statistics table.

Because the traffic we're tracing is multicast, the next handler function is

With some exotic locking in place, the kernel determines how many different sockets this multicast packet needs to be delivered to. It is worth noting here that there is a smallish number (

An effort is made to enumerate the registered sockets with a lock held, then perform the packet dispatching without a lock. However, if the number of registered sockets exceeds the specified threshold, then packet dispatch (the

Once in

If the kernel is unable to allocate memory in order to copy the buffer, the socket's drop-count will be incremented, along with the

After another checksum test, we are finally at the point where socket-buffer overflow is tested:

If the size of the socket's backlog queue, plus the memory used in the receive queue is greater than the socket receive buffer size, then the

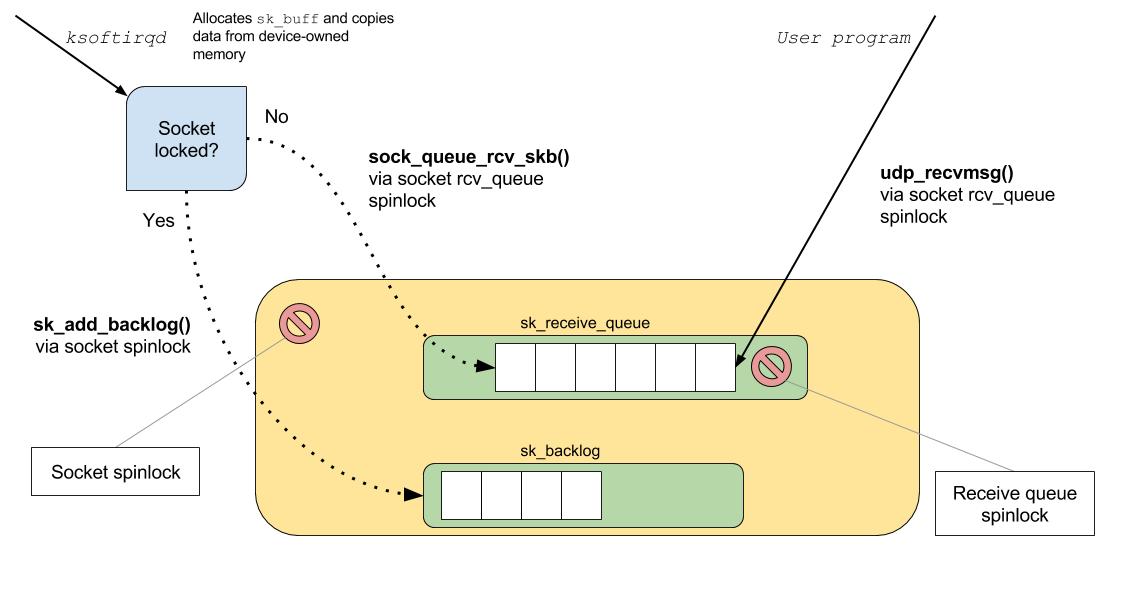

To safely handle multi-threaded access to the socket buffer, if an application has locked the socket, then the inbound packet will be queued to the socket's backlog queue. The backlog queue will be processed when the lock owner releases the lock.

Otherwise, pending more checks that socket memory limits have not been exceeded, the packet is added to the socket's

Finally, once the packet has been delivered to the socket's receive queue, notification is sent to any interested listeners.

Now that we have seen where the various capacity checks are made, we can make some observations in the

There are protocol-specific files in

This file contains statistics on multiple protocols, and is the target for updates to the UDP receive buffer errors. So when we want to know about system-wide receive errors, this is the place to look. When this file is read, a function call iterates through the stored values and writes them to the supplied destination. Such is the magic of

In the output below, we can see that there have been several receive errors (

Each of the columns maps to a constant specified here, so to determine when these values are updated, we simply need to search for the constant name.

There is a subtle difference between

This file contains socket-specific statistics, which only live for the lifetime of a socket. As we have seen from the code so far, each time the

So if we need to differentiate between drop events on a per-socket basis, this file is what we need to observe. The contents below can be explained by looking at the handler function for socket data:

For observing back-pressure, we are interested in the drops column, and the rx_queue column, which is a snapshot of the amount of queued data at the time of reading. Local and remote addresses are hex-encoded

Monitoring this file can tell us if our application is falling behind the packet arrival rate (increase in

If we wish to capture more data about packets that are being dropped, there a three tracepoints that are of interest.

These events can be captured using Linux kernel tracing tools such as

Let's just recap the points of interest for monitoring throughput issues in the network receive path.

Follow @epickrram

At the end of the last post, I mentioned that application back-pressure was most likely to be the cause of receiver packet-loss. As we continue through the code path taken by inbound packets up into user-land, we will see the various points at which data will be discarded due to slow application processing, and what metrics can shed light on these events.

Protocol mapping

First of all, let's take a quick look at how a received data packet is matched up to its handler function.

We can see from the stack-trace below that the top-level function calls when dealing with the packets are

packet_rcv and ip_rcv:__netif_receive_skb_core() {

packet_rcv() {

skb_push();

__bpf_prog_run();

consume_skb();

}

bond_handle_frame() {

bond_3ad_lacpdu_recv();

}

packet_rcv() {

skb_push();

__bpf_prog_run();

consume_skb();

}

packet_rcv() {

skb_push();

__bpf_prog_run();

consume_skb();

}

ip_rcv() {

...

__bpf_prog_run function call, which indicates that this is the entry point for pcap packet capture and filtering.The protocol-to-handler mapping can be viewed in the file

/proc/net/ptype:

[pricem@metal]$ cat /proc/net/ptype

Type Device Function

ALL em1 packet_rcv

0800 ip_rcv

0011 llc_rcv [llc]

0004 llc_rcv [llc]

88f5 mrp_rcv [mrp]

0806 arp_rcv

86dd ipv6_rcvComparing against this reference, it is clear that the kernel reads the value of the ethernet frame's

EtherType field and dispatches to the corresponding function. There are also some functions that will be executed for all packet types (signified by type ALL).So our inbound packet will be processed by the capture hooks, even if no packet capture is running (this then must presumably be very cheap), before being passed to the correct protocol handler, in this case

ip_rcv.The socket buffer

ip_rcv starts by getting its own copy of the incoming packet, copying if the packet is already shared. If the copy fails due to lack of memory, then the packet is discarded, and the Discard count of the global ip statistics table is incremented. Other checks made at this point include the IP checksum, header-length check and truncation check, each of which update the relevant metrics.Before calling the

ip_rcv_finish function, the packet is diverted through the netfilter module where software-based network filtering can be applied.Assuming that the packet is not dropped by a filter,

ip_rcv_finish passes the packet on to the next protocol-handler in the chain, in this instance, udp_rcv.In the internals of the

udp_rcv function, we finally get to the point of accessing the socket FIFO queue.Simple validation performed at this point includes packet-length check and checksum. Failure of these checks will cause the relevant statistics to be updated in the global udp statistics table.

Because the traffic we're tracing is multicast, the next handler function is

__udp4_lib_mcast_deliver.With some exotic locking in place, the kernel determines how many different sockets this multicast packet needs to be delivered to. It is worth noting here that there is a smallish number (

256 / sizeof( struct sock)) of sockets that can be listening to a given multicast address before the possibility of greater lock-contention creeps in.An effort is made to enumerate the registered sockets with a lock held, then perform the packet dispatching without a lock. However, if the number of registered sockets exceeds the specified threshold, then packet dispatch (the

flush_stack function) will be handled while a lock is held.Once in

flush_stack, the packet is copied for each registered socket, and pushed onto the FIFO queue.If the kernel is unable to allocate memory in order to copy the buffer, the socket's drop-count will be incremented, along with the

RcvBufErrors and InErrors metrics in the global udp statistics table.After another checksum test, we are finally at the point where socket-buffer overflow is tested:

if (sk_rcvqueues_full(sk, sk->sk_rcvbuf)) {

UDP_INC_STATS_BH(sock_net(sk), UDP_MIB_RCVBUFERRORS,

is_udplite);

goto drop;

}If the size of the socket's backlog queue, plus the memory used in the receive queue is greater than the socket receive buffer size, then the

RcvBufferErrors and InErrors metrics are updated in the global udp statitics table, along with the socket's drop count.To safely handle multi-threaded access to the socket buffer, if an application has locked the socket, then the inbound packet will be queued to the socket's backlog queue. The backlog queue will be processed when the lock owner releases the lock.

Otherwise, pending more checks that socket memory limits have not been exceeded, the packet is added to the socket's

sk_receive_queue.Finally, once the packet has been delivered to the socket's receive queue, notification is sent to any interested listeners.

Kernel statistics

Now that we have seen where the various capacity checks are made, we can make some observations in the

proc file system.There are protocol-specific files in

/proc/net that are updated by the kernel whenever data is received.

/proc/net/snmp

This file contains statistics on multiple protocols, and is the target for updates to the UDP receive buffer errors. So when we want to know about system-wide receive errors, this is the place to look. When this file is read, a function call iterates through the stored values and writes them to the supplied destination. Such is the magic of

procfs.In the output below, we can see that there have been several receive errors (

RcvbufErrors), and the number is matched by the InErrors metric:Udp: InDatagrams NoPorts InErrors OutDatagrams RcvbufErrors SndbufErrors InCsumErrors

Udp: 281604018683 4 261929024 42204463516 261929024 0 0Each of the columns maps to a constant specified here, so to determine when these values are updated, we simply need to search for the constant name.

There is a subtle difference between

InErrors and RcvbufErrors, but in our case when looking for socket buffer overflow, we only care about RcvbufErrors.

/proc/net/udp

This file contains socket-specific statistics, which only live for the lifetime of a socket. As we have seen from the code so far, each time the

RcvbufErrors metric has been incremented, so too has the corresponding sk_drops value for the target socket.So if we need to differentiate between drop events on a per-socket basis, this file is what we need to observe. The contents below can be explained by looking at the handler function for socket data:

[pricem@metal ~]# cat /proc/net/udp

sl local_address rem_address st tx_queue rx_queue ... inode ref pointer drops

47: 00000000:B87A 00000000:0000 07 00000000:00000000 ... 239982339 2 ffff88052885c440 0

95: 4104C1EF:38AA 00000000:0000 07 00000000:00000000 ... 239994712 2 ffff8808507ed800 0

95: BC04C1EF:38AA 00000000:0000 07 00000000:00000000 ... 175113818 2 ffff881054a8b080 0

95: BE04C1EF:38AA 00000000:0000 07 00000000:00000000 ... 175113817 2 ffff881054a8b440 0

...For observing back-pressure, we are interested in the drops column, and the rx_queue column, which is a snapshot of the amount of queued data at the time of reading. Local and remote addresses are hex-encoded

ip:port addresses.Monitoring this file can tell us if our application is falling behind the packet arrival rate (increase in

rx_queue), or whether the kernel was unable to copy a packet into the socket buffer due to it already being full (increase in drops).Tracepoints

If we wish to capture more data about packets that are being dropped, there a three tracepoints that are of interest.

sock:sock_rcvqueue_full: called when the amount of memory already allocated to the socket buffer is greater than or equal to the configured socket buffer size.sock:sock_exceed_buf_limit: called when the kernel is unable to allocate more memory for the socket buffer.udp:udp_fail_queue_rcv_skb: called shortly after thesock_rcvqueue_fullevent trace for the same reason.

These events can be captured using Linux kernel tracing tools such as

perf or ftrace.Summary

Let's just recap the points of interest for monitoring throughput issues in the network receive path.

/proc/net/softnet_stat: contains statistics updated by the ksoftirq daemon. Useful metrics are processed, timesqueeze and dropped (discussed in detail in the last post)./proc/net/snmp: contains system-wide statistics for IP, TCP, UDP. Useful metrics indicate memory exhaustion, buffer exhaustion, etc./proc/net/udp: contains per-socket information. Useful for monitoring queue depths/drops for a particular socket./proc/net/dev: contains statistics provided by network devices present on the system. Some supplied statistics are driver-specific./sys/class/net/DEV_NAME/statistics: provides more detailed statistics from the network device driver.

Follow @epickrram